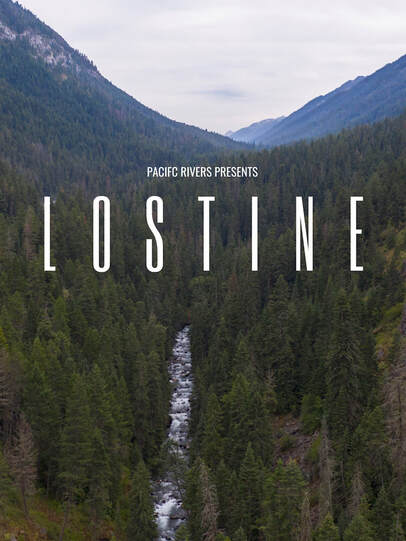

The Lostine River’s Salmon Need a Free-Flowing Lower Snake Rive

Oregon’s Lostine River is a headwater stream of the Grand Ronde River watershed, which in turn is a major tributary of the Snake River Basin. In addition to the conservation easements within the Wolfe Century Ranch, sixteen miles of the upper Lostine River are also permanently protected by National Wild and Scenic Rivers Act designation.

While the Lostine River still contains exceptional salmon habitat, and the remarkable recent success of Chinook Salmon in the river is profoundly encouraging, the largest challenge still facing these incredible fish remains their dangerous journey through the eight massive hydropower dams on the Lower Snake and Columbia Rivers. The Lostine River Weir is located 600 miles from the Pacific Ocean and every salmon returning here makes that journey twice: once as a juvenile and once as a returning adult.

The Snake River Basin’s Spring and Fall Chinook are both listed as Threatened under the Endangered Species Act. Scientists have been telling us for decades that the best chance to recover these fish before they slip further towards extinction is to remove the four destructive dams on the Lower Snake River. This would vastly improve the survival rates of juvenile fish during their migration to sea.

Today, throughout the Snake River Watershed, imperiled populations of salmon continue to die at rates far below sustainable replacement levels. Because the stagnant reservoirs behind the dams roast in the sun all Summer long, the water frequently hits temperatures lethal to salmon. A free-flowing lower Snake River would be substantially cooler during crucial months for juvenile and adult salmon migration, an important consideration for the future of these fish as the climate continues to warm.

After generations of lost time and billions of dollars of failed mitigation efforts, the time has come for elected leaders to finally take the steps necessary to breach these unnecessary dams and restore the region’s salmon before we lose the fish that define the region’s ecology and cultural heritage. We can’t allow efforts and collaborations like those occurring on the Lostine River to be wasted.

While the Lostine River still contains exceptional salmon habitat, and the remarkable recent success of Chinook Salmon in the river is profoundly encouraging, the largest challenge still facing these incredible fish remains their dangerous journey through the eight massive hydropower dams on the Lower Snake and Columbia Rivers. The Lostine River Weir is located 600 miles from the Pacific Ocean and every salmon returning here makes that journey twice: once as a juvenile and once as a returning adult.

The Snake River Basin’s Spring and Fall Chinook are both listed as Threatened under the Endangered Species Act. Scientists have been telling us for decades that the best chance to recover these fish before they slip further towards extinction is to remove the four destructive dams on the Lower Snake River. This would vastly improve the survival rates of juvenile fish during their migration to sea.

Today, throughout the Snake River Watershed, imperiled populations of salmon continue to die at rates far below sustainable replacement levels. Because the stagnant reservoirs behind the dams roast in the sun all Summer long, the water frequently hits temperatures lethal to salmon. A free-flowing lower Snake River would be substantially cooler during crucial months for juvenile and adult salmon migration, an important consideration for the future of these fish as the climate continues to warm.

After generations of lost time and billions of dollars of failed mitigation efforts, the time has come for elected leaders to finally take the steps necessary to breach these unnecessary dams and restore the region’s salmon before we lose the fish that define the region’s ecology and cultural heritage. We can’t allow efforts and collaborations like those occurring on the Lostine River to be wasted.

Columbia/Snake Salmon Recovery Campaign

The mighty Columbia and Snake Rivers define the Northwest. They once produced the greatest salmon runs on Earth, sustaining native cultures, ecosystems and economies since time immemorial. Today, just a small number of wild fish return to only a fraction of their historic habitat. Despite their size, the rivers are not immune to the effects of climate change, as we saw in 2015, when thousands of sockeye perished on their way up the Columbia because the river was too warm.

But it’s not just salmon that are impacted by dams. The Southern Resident Orca population, also critically endangered, relies on Chinook salmon from the Columbia and Snake for a critical part of their winter diet, when they intercept the fish off the mouth of the Columbia. But the fish aren’t there in the numbers needed to feed pregnant females and the population is perilously close to going extinct.

But it’s not just salmon that are impacted by dams. The Southern Resident Orca population, also critically endangered, relies on Chinook salmon from the Columbia and Snake for a critical part of their winter diet, when they intercept the fish off the mouth of the Columbia. But the fish aren’t there in the numbers needed to feed pregnant females and the population is perilously close to going extinct.

A Basin-Wide Strategy

Pacific Rivers’ has a basin-wide strategy focused on flows, temperature, water quality and passage to recover salmon, help Orca and restore communities that depend on healthy rivers. We’re advocating for more flow from Canadian dams through the renegotiation of the Columbia River Treaty in order to help juvenile salmon get to the sea and keep the river cool. Treaty renewal also creates an opportunity to support fish passage and reintroduction to areas currently blocked in both the U.S. and Canada. Another area of focus is the relicensing of the Hells Canyon Complex, three dams on the mid Snake River in Idaho and Oregon. These dams block fish passage, have changed the flow and temperature of the river, and create the conditions for toxic levels of mercury to accumulate in resident fish, which the government advises not to eat. The new license for the project will last 50 years, which is why our involvement is critical for ensuring the impacts of the dams is addressed equitably.

In the lower Snake, we are working with a broad coalition that seeks the removal of four federal dams in Washington state. These dams slow the river and increase its temperature, making conditions ripe for disease and predators, which threaten young salmon migrating to the ocean. Fortunately, political winds are shifting and the region is beginning to shape the contours of what could be the biggest river restoration project in history.

In the lower Snake, we are working with a broad coalition that seeks the removal of four federal dams in Washington state. These dams slow the river and increase its temperature, making conditions ripe for disease and predators, which threaten young salmon migrating to the ocean. Fortunately, political winds are shifting and the region is beginning to shape the contours of what could be the biggest river restoration project in history.